Well, I left Brunswick, GA and sailed north. Just not very far.

My original plan was to voyage solo to Charelston, SC (about 150 miles), spend a wet, windy weekend anchored off the city marina, and then pick up my friend Ed on Monday. We would then point the bow toward Beaufort, NC and make a big jump to position Laughing Gull just south of Hatteras. Unfortunately, the weather forecast called for strong easterlies throughout our weather window, which didn’t sound like much fun. So I waved Ed off and executed Plan B: a coastal hop up to Hilton Head.

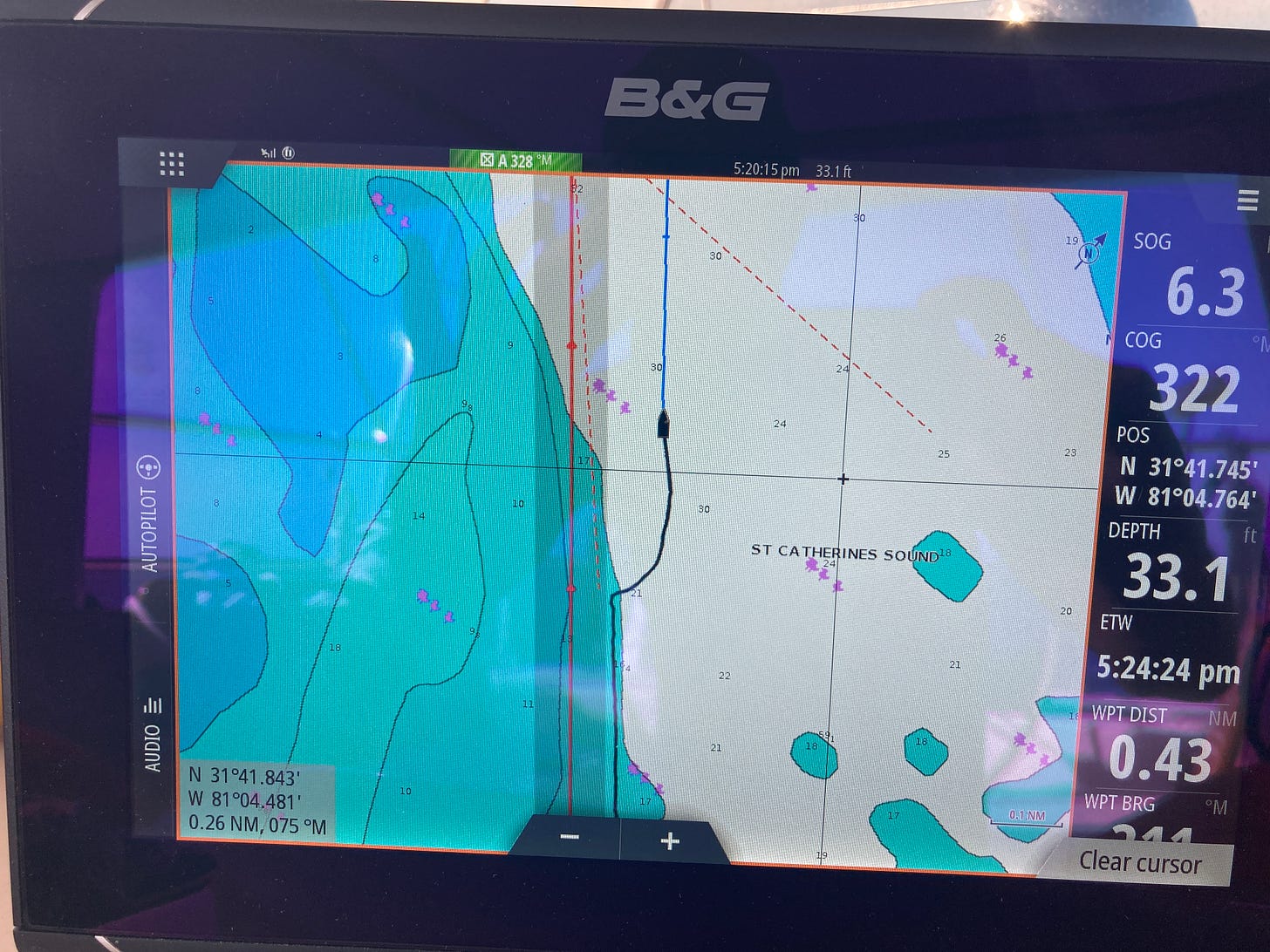

I spent the first night anchored on the Walburg River off St. Catherine’s Sound, and discovered that poking into the inlets of the southeastern Atlantic coast involves true seat-of-the-pants navigation. Most, perhaps all, of the buoys that are indicated on your chart will be missing. And very often the depth soundings are wrong, too. Sometimes by a lot. You have to go slow, try to enter on a rising tide, and believe what your eyes might be telling you about the color of the water. I almost ran aground when I relaxed after passing what appeared to be the shallowest part of the inlet entrance and glanced up to see the depth sounder rapidly plummeting from 10, to 7, to 5 (which is inches from putting my keep into the mud—the depth sounder transducer is about 2 feet below the waterline). I raced to turn the autopilot off and made a quick 90-degree turn toward what I hoped was deeper water. Embarrassment averted, barely. I was annoyed with myself for losing focus, but in my defense my chart did indicate that there should have been 17 of depth in that spot. Anyhow, once you lose all faith in the charted soundings you are truly back in the 19th century. Which adds an element of stress and suspense that is unusual in modern-day digital boating, but also made my sundowner, once finally and safely on the hook, all the sweeter.

Overnight was peaceful and calm, with no other boats nearby. I left as the sun was rising, and felt my way back out the inlet, this time with full concentration and no near misses. Unfortunately, there was almost no wind, so I was a motorboat all morning. As I had been for a good part of the previous day, which in total meant about 20 gallons of diesel burned (probably more than I would use in a month of driving). I contemplated this sad state of affairs, and came to a realization: if I really want to minimize the use of diesel, and connect more honestly with the ocean world, I have to stop relying on the convenience of a combustion engine to get where I want to go on a schedule. The ease of firing up the diesel to keep my speed up, catch the tide, or arrive somewhere before sundown, is very hard to resist. But it is a kind of cheating, and it is a kind of cheating that involves doing something that I want to do a lot less of: spewing carbon. Motoring along on a flat sea with not much happening is a good time to self-reflect. And I decided I need to set a much higher bar for using my engine. Motoring for safety reasons (say to find shelter ahead of a storm) would meet the new threshold. Motoring for convenience would not.

This felt like a solid and constructive conclusion to my conference with myself. And if retroactively applied to my hop north to Hilton Head would have resulted in an entirely different plan and experience. Instead of breaking the voyage into two daysails (or motors, as it turned out), and a night at anchor, with the forecast for very light winds I would have departed Brunswick and sailed through the night for Hilton Head. I would have often been sailing slowly, and probably would have drifted at times. But by not stopping anywhere, I would have arrived off Tybee Roads (the entrance to the Savannah River and Hilton Head’s Calibogue Sound from the south) in plenty of time to beat the foul weather ahead. I would not have been able to explore St. Catherine’s Sound. But there is also reward in peacefully ghosting through a warm night, with plenty of stars and a waning moon to keep you company. Doing so defers to wind and weather, which increasingly feels right to me. Pushing a button to start a diesel is humankind’s way of refusing to defer, and separating ourselves from the landscapes we travel across. Which is damaging both to our relationship with those landscapes and to the landscapes themselves.

Now, I don’t want to get carried away, or come off the wrong way. I can think of a million reasons why a million different people in a million different circumstances might have good reason to push that button or turn that key. And I will use the motor, too, of course, when I need it. All I know is that in my own circumstances I can change the calculus, and modify my approach so “need” is much more narrowly defined. I think I will be better for it, and I’ll have to learn to think differently, more humbly and more strategically, so that going slowly, missing a tide, or not getting as far as I had hoped, will simply be a circumstance and not a source of frustration. Perhaps there will be a kind of spiritual deepening that comes from acknowledging and accepting the power of the natural forces that drive wind, tide and sea, rather than defying and diminishing those forces with the alternate reality of a combustion engine. I have always loved a saying about the weather, frequently repeated by the great racing sailor Carleton Mitchell: “You eats what the cook serves.” Committing to that profound idea is committing to a different way of voyaging and seeing the world. We’ll see how it goes.

Mitchell said something else which resonates deeply with me, worth mentioning here I think. “To desire nothing beyond what you have is surely happiness. Aboard a boat, it is frequently possible to achieve just that.” Amen.

Odds And Ends:

—A beautiful homage to the albatross…and a stark warning about how industrial fishing threatens its future.

—Lost At Sea: a suspenseful BBC podcast about the mysterious disappearance of a fisheries observer.

—So true…

If you liked this post from Sailing Into The Anthropocene, why not subscribe here (free!), and/or hit that share button below? You can also find me on Instagram and Twitter.

I wish more boaters had your sensibility, especially when it comes to the need for speed.

Appreciate your principled approach to sailing