All good things come to an end. Or at least they are supposed to. So I left my private paradise in Ensenada Honda last Wednesday. The reason: I had to get 25 miles east by Sunday, and on Wednesday the wind was predicted to go SSE, and moderate to 12-15 knots. On paper that is a perfect forecast for trying to forge your way ENE in the Caribbean. To show my respect and gratitude, I took the gift the Wind Gods offered, and weighed anchor before 8 am. The part of me that loves solitude, peace, and untrammeled (though ironically not unbombed) Nature, had some regrets to be outbound. The sailor in me, however, was looking forward to making fast miles across a cobalt sea in a well-found boat.

I raised the full main in flat water before clearing Ensenada Honda, knowing I would need power in the lighter wind ranges expected. One of the things I love about Laughing Gull’s flexible cutter rig, with two different sized headsails on furlers, is that is is easy to switch gears, and power up or down, as needed. She is comfortable with full main and the (smaller) staysail up to around 18-20 knots of wind, depending on the sea state. Above that, some reef in the main settles things down nicely.

I started off on port tack, heading south, because I needed to get an angle to clear the eastern tip of Vieques before pointing the bow at St. John, my goal for the day. It was a picture-postcard Caribbean tableau. Fluffy white cumulonimbus clouds, an azure sky, a cobalt ocean, and solid breeze. The Caribbean rarely offers nicer sailing conditions. I even had a pair of Brown Boobies flying escort for a while.

Still, LG was working—punching into 3-5 foot swells from the southeast, burying her bow into the bigger sets, sending cascades of water down the deck, and squirting through the aging seals of the forward hatches. The motion was, um, vigorous (happily, by now I have learned to stow everything below securely before leaving an anchorage, no matter how friendly the forecast seems). The breeze was up and down enough that I found myself switching gears, furling and unfurling the staysail and genoa, more than a mildly lazy person might like. Plus, all the action was reminding my ribs that they had been assaulted by a bow cleat, and they should speak up. So they started squawking.

I was on the verge of complaint myself, when the wind graciously flicked south twenty favorable degrees. I immediately tacked onto starboard. LG’s bow was now pointed directly at St. John, we were doing a solid 7-8 knots, and all was suddenly well again in the world. There was still plenty of messing around with the headsails to keep things in the speed/comfort zone, which at least led me to a new sail combo that I really liked (full staysail, and genoa unfurled and reefed in and out as necessary, an even simpler way of changing gears).

I worked up a good sweat. My ribs hated me. The sun tried to put a good sear into my epidermal outer layer, no matter how much I tried to stay out of it (it was almost enough to give me second thoughts about my preference for not wearing sunscreen).

A truth about Caribbean sailing, which I had kind of been working on deep in my mind for a few months now, clarified and became concrete. It is an echo of military theorist Karl Von Clausewitz’s famous observation that “Everything is very simple in war. But the simplest thing is difficult.” My version is: “There is easier weather and harder weather in the Caribbean. But even easy weather requires some hard sailing.” This is true because “easy” weather down here usually means winds of around 15 knots (which is when many or most boats reef), there is almost always good-sized swell (you are lucky if it is down to 2-4 feet), and the sun, and popup squalls, can be relentless. In contrast, easy weather on the northeast Atlantic coast for example, means 10-12 knots of wind, flat water, and no chance of squalls. You are laughing and relaxing all the way to anchor.

Don’t get me wrong: it was grand sailing. It is just that it is never really that mellow down here when underway. This reality can make singlehanding a 50-foot sailboat in the tradewind zone more of an effort than singlehanding elsewhere (of course, at least during the winter, you are not worrying about storms and tropical systems like you do elsewhere). Which is fine. It is still a great pleasure, and gives me a feeling of freedom and connection that I don’t find elsewhere. And cruising here requires way less diesel fuel consumption than other regions, in which very light winds are much more common. But sailing here is not what most people think it is. It is challenging in its own way, and pretty easy to spill your rum drink if you are not careful.

I arrived in the Caneel Bay mooring field by mid-afternoon, grateful for a weather window that had required only one tack to make my way east. I was happy to be back in St. John, now very high on my list of favorite places. I wasn’t fully at ease, though. It is a little strange to be so distant, and on a sailboat, from everything that is happening in the United States (with its enormous impact on the rest of the world and its future). Perhaps that distance makes it easier to avoid dark, doomy, feelings, because the zeitgeist around you is not obsessing about politics and heartbreak. And perhaps it allows more room to think clearly about what any individual can do (I have some ideas beyond flying an upside down American flag). But it still feels slightly off, a bit like living abroad during a moment of deep change and inflection in American history.

Speaking of: flag update. I have yet to see another boat flying an upside-down American flag in protest to the ongoing assault on the Constitution and Rule of Law. But the skipper of a boat motoring past me in Caneel Bay noted my flag and called out to say he was with me. So that was a nice small tremor of solidarity. I get that it feels uncomfortable, or perhaps even a bit scary, for patriotic Americans to deliberately use the flag as a form of protest. I hesitated as well. But these are times that require courage and clear statement. So I am still hopeful others will join in this form of protest.

Anthropocene Notes:

Sperm whales are awesome: I tend to feel humans (researchers, filmmakers, tourists) are too often invading the lives and spaces of whales and other charismatic marine mammals. At the same time, good filmmaking can make a difference in how humanity sees and treats other species.

“Patrick And The Whale,” a PBS Nature special, takes viewers inside the connection a filmmaker made with a curious and engaging female sperm whale. It’s a great insight into how little we understand or appreciate the complexity and magnificence of so many of the animals we are endangering or harming. Here’s the trailer (lots more clips here):

Climate Justice still matters: It may be under assault in Trump 2.0, but Cass Sunstein, a brilliant and innovative scholar, makes a powerful case for the moral imperative that requires wealthy nations (especially the US) to care about how our actions affect the lives and well-being of others around the globe:

In his new book, “Climate Justice: What Rich Nations Owe the World — and the Future,” the legal scholar Cass Sunstein cites one estimate that, since 1990, carbon from the world’s five largest emitters is responsible for $6 trillion in income loss around the world. Some researchers have suggested that damage from that already-emitted carbon could grow 80-fold over this century. According to calculations by Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency, the “social cost of carbon” from the United States alone reaches $1 trillion in yearly damages globally. Other estimates run higher.

Can we just ignore that? I don’t think so. I just ordered Sunstein’s book on Kindle, and look forward to reading it.

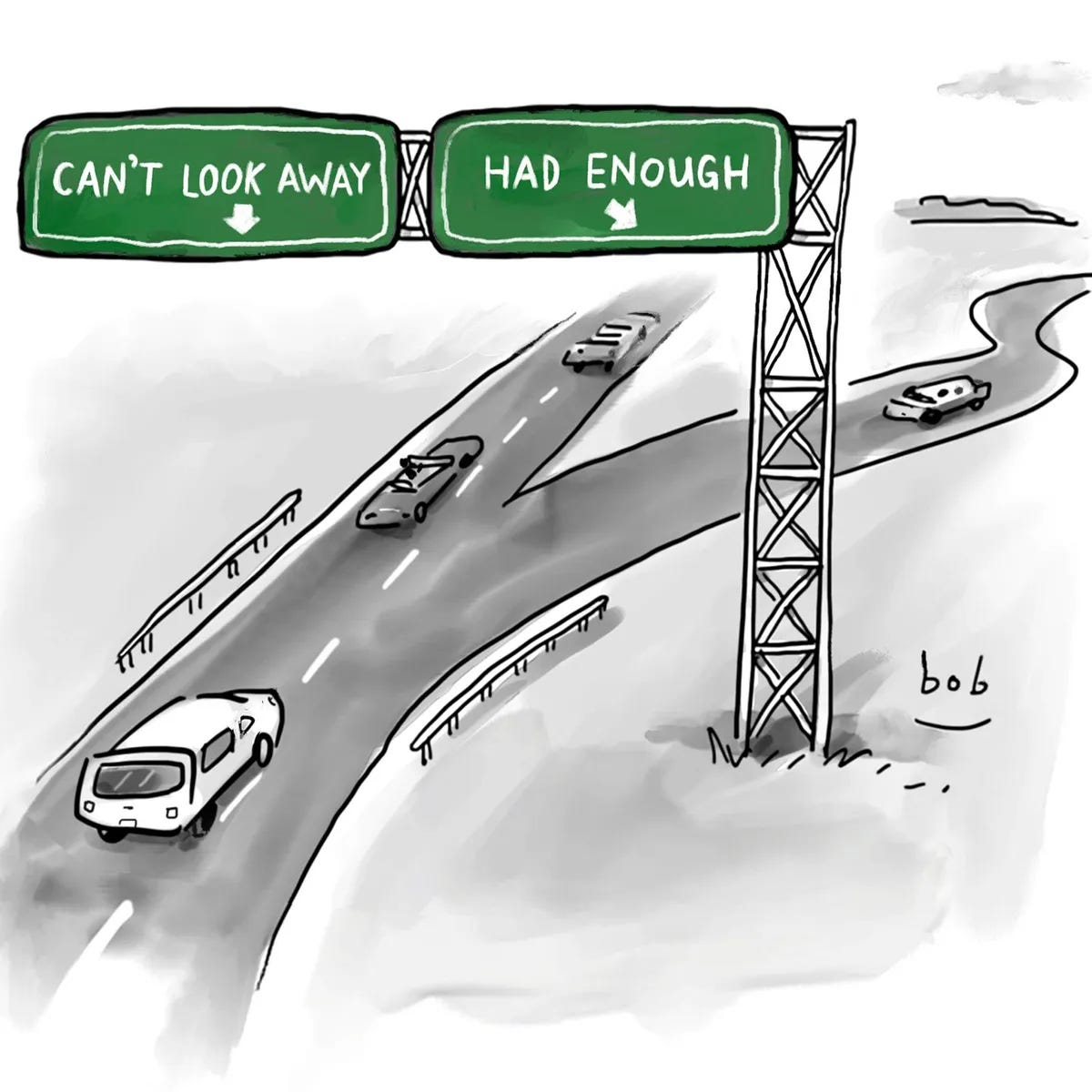

Dilemma Of The Moment: Don’t look away is my advice, even though that offramp is pretty tempting.

If you liked this post from Sailing Into The Anthropocene, why not subscribe here (free!), and/or hit that share button below? You can also find me on Instagram and BlueSky.