When I arrived back aboard Laughing Gull 10 days ago I was welcomed by a spectacular sunset view of Montserrat, with its distinctive volcano plume. I cracked a cold beer, and soaked up the tropical warmth after frigid temps and lots of shoveling snow back north. I went to bed early and slept deeply through a calm, peaceful night on the mooring, with stars blazing overhead and a luminescent moon working its way toward full.

These are the sorts of moments that are unique to life afloat, and exactly the sort of moments—along with cocktails, beaches, easy sailing, and unmatched solar shenanigans—that most of the non-cruising world imagines as the baseline of life aboard a sailboat. To those who do not live afloat, it is a life of ease and pleasure, a self-indulgent way of being that serves no ideals or broader good. It is easy to dismiss or disparage flippantly, because it involves something that can be called a “yacht.” At least that is what I can infer from the harsher judgments about what I am doing that filter my way.

I don’t want to litigate my choices with regard to a broader purpose. I have already explained that being on a sailboat is how I choose to live simpler and shrink my (climate and environmental) footprint, two ideals that are important to me. These are things anyone can do, wherever they live (though the relatively limited space in a sailboat helps compel some of the changes required), if they choose. And if writing about why I do what I am doing (and why the choices I make feel right and often improve my energy, happiness, and connection to the planet), raises even a single question in a single mind about whether there might be a better way to live than the way modern culture, capitalism, and marketing wants humans to live, then I am content that I am not just out here on my own, voiceless and irrelevant.

What I do want to clarify, though, is the assumption that life aboard a boat is easy. It is an easy (and necessary) choice for me to make. But the actual living? The actual living ain’t that easy.

I’ve been musing on this since I returned to the boat, because I spent the morning after arrival sweating and twisted half upside down under the galley sink, trying to fix a persistent leak in the freshwater pressure system. For a moment it appeared that I would only succeed in making the problem worse, one of the inevitable risks of attempting any repair on a boat. And all I would have to show for it was bloody scrapes on the knuckle of my right hand “If they could see me now,” I thought.

Happily, in the end I managed to improve the situation, which feels good in any home. But the gremlins in the boat kept rallying, and assaulting my peace of mind. The windlass, a vital, vital piece of equipment, started to make an ominous thunking sound. So into the anchor locker in the bow I went, to do more boat yoga. There, I disassembled and re-assembled the windlass undercarriage, tightening all the fasteners and crossing my fingers that would do the trick. Ah, life in paradise.

From the windlass, it was on to yet another attempt to seal a small leak in the inflatable dinghy floor. My humble commuter vehicle is a much more efficient watercraft, whether propelled by oars or the outboard, if the floor is rigid. Plus, it is tedious to have to pump it up again with every use. On this one, sadly, the gremlins scored a counterpoint. Despite great hope after I layered on another slab of goop over the pinprick leak the floor slowly hissed itself back into a semi-flaccid state.

These are all good examples of the chores and repairs that lead sailors to quip that liveaboard cruising is simply fixing your boat in beautiful places. Every sailboat has a job list. Every sailor works tirelessly to reduce the job list. But no one ever clears the job list, and it rarely shrinks. A growing boatwork list can overwhelm and even depress. Which is all to say that living on a boat is not like living in some alternate reality, where bad luck and trouble are somehow banished. It is a lot like living in lots of places. Full of adversity, challenge, and, sometimes, real suffering (my heart goes out to all Los Angelenos). Perhaps the high points afloat are higher, but there is a relentless baseline of adversity and vulnerability that means you are rarely fully relaxed. That takes a lot of getting used to. Now that I have been boat-lifing for more than a year I can’t honestly think of many people I know who could do it.

Life aboard Laughing Gull did eventually settle down a bit, and I headed south to Guadeloupe. But the gremlins weren’t quite done. While moored at Ilet De Cabrit in Les Saintes (a beautiful area), and settling in for the night, there was an almighty bang, massive vibration in the rig, and the sound of something metal hitting the deck. All very, very, bad sounds, which at first had me thinking that one of the shrouds holding the rig up had failed. I rushed on deck, expecting disaster. The mast still stood. All the rigging remained in place and under normal tension. I couldn’t find any parts on the deck.

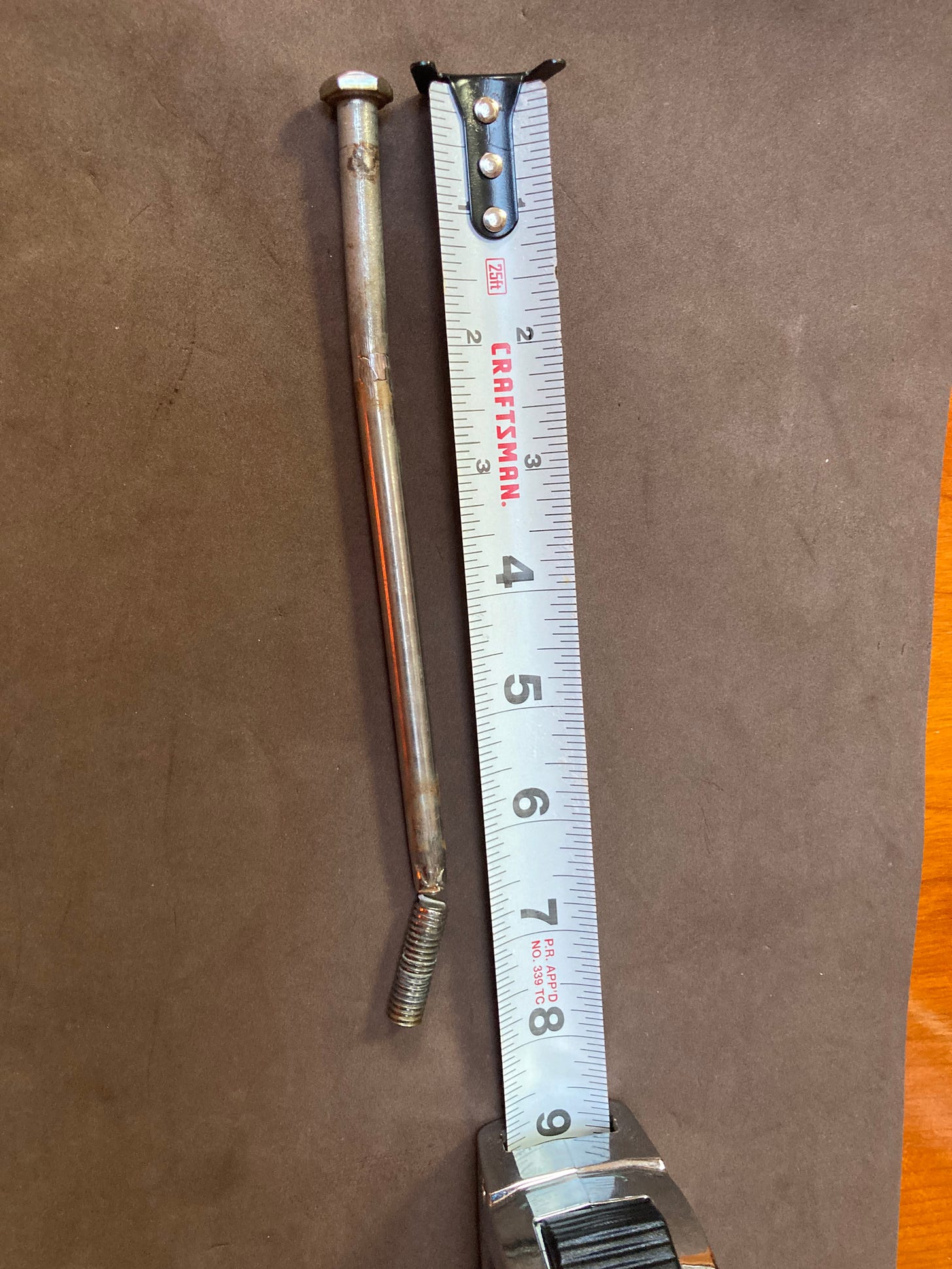

I spent the night, tossing and turning, wondering what had happened, and whether I could sail anywhere safely without knowing exactly what had transpired. In the morning I walked the deck again and found the end of a sheared bolt. I got my binoculars and looked up the mast. I could see the other end of the bolt protruding from the bracket which attaches the lower spreaders to the mast. I don’t have a spare, so I ordered one. Until I receive it and install it, I will have to sail with care and hope that the other seven fasteners in the spreader brackets are sufficient to do the job. As to what caused the rig to vibrate and the bolt to shear, I can come to only one conclusion: in the dark, one of the large pelicans working the shoreline must have flown into the rig. Worse for him than for me, probably. Still, it is always something out here.

Mystery solved, this afternoon I ran up and down a hill on a deserted island with a fortress on top, scattering lizards and hermit crabs, and then swam back to the boat. Adversity does have a reward.

Anthropocene Notes:

An early scientific assessment calculates the role of climate change in the catastrophic LA fires:

Key Takeaways:

Climate change may be linked to roughly a quarter of the extreme fuel moisture deficit when the fires began.

The fires would still have been extreme without climate change, but probably somewhat smaller and less intense.

Given the inevitability of continued climate change, wildfire mitigation should be oriented around (1) aggressive suppression of human ignitions when extreme fire weather is predicted, (2) home hardening strategies, and (3) urban development in low wildfire risk zones.

Accuweather estimates more than $250 billion in damage and economic loss. Ongoing losses from climate-turboed disasters will continue to drive up insurance costs for every home and auto owner, and drive private insurers out of many markets. That is the sort of impact on wallets that changes voting patterns.

The Supreme Court declined to protect oil and gas companies from lawsuits tat seek to hold them liable for the damages of climate change:

The order allows the city of Honolulu’s lawsuit against oil and gas companies to proceed. The city’s chief resilience officer, Ben Sullivan, said it’s a significant decision that will protect “taxpayers and communities from the immense costs and consequences of the climate crisis caused by the defendants’ misconduct.”

The industry has faced a series of cases alleging it deceived the public about how fossil fuels contribute to climate change. Governments in states including California, Colorado and New Jersey are seeking billions of dollars in damages from things like wildfires, rising sea levels and severe storms. The lawsuits come during a wave of legal actions in the U.S. and worldwide seeking to leverage action on climate change through the courts.

This is another way change will finally come. Legal accountability.

A fascinating article on how global sports contribute to climate change, and will be impacted by climate change. Big climate polluters? The World Cup, the Olympics and…golf.

Most threatened? Skiing (no surprise there), but also anything outside in the summer is surprisingly vulnerable:

Outdoor sports have gotten dangerous. The women’s marathon at the 2019 World Athletics Championship in Qatar started at 11.59pm to avoid the worst of the heat. Even so, over 40% of starters failed to finish the course. During the Tour de France, traditionally held in July, organizers faced with cyclists suffering heatstroke spray roads with water to reduce temperatures—hardly an option for recreational riders. And some hazards no money can protect from. At least one player in the 2020 Australian Open tennis championship retired after breathing wildfire smoke.

4. This about right?

If you liked this post from Sailing Into The Anthropocene, why not subscribe here (free!), and/or hit that share button below? You can also find me on Instagram and BlueSky.

I think it is reality. In a home I had a list, but not a very dynamic one and hardly ever urgent. The salty environment, plus bouncing around a lot, plus lots of systems, makes for more stiff that can fail. To me there is simply greater underlying adversity—that ranges from minor to potentially catastrophic. And also a low intensity, but chronic, sense of vulnerability. They are worth dealing with for all the positive aspects of life aboard, but definitely hard to fully appreciate for someone who hasn’t lived that way

"Now that I have been boat-lifing for more than a year I can’t honestly think of many people I know who could do it." It has always seemed to me, too, that more things go wrong with my home afloat than ever did on solid ground. I wonder if that's perception or reality?