Trying something a little different…

June 27. Mattapoisett, MA:

Back onboard Laughing Gull after the Newport-Bermuda Race. Sailed on The Rover, my friend Steve’s very well-prepared Swan 44 MK II. The crew was great, the conditions (brisk wind ahead of the beam, sloppy seas) favored a Swan, and we finished 9th overall of 98 boats. So a pretty good result.

We failed to make it to Bermuda in 2022, and this edition—with its windy, wet, conditions—featured many retirements, including a dismasting and two boats abandoned and sunk. So it felt like a victory simply to arrive at the finish line in one piece.

I still love the tactics and camaraderie of racing, but over the past two years aboard Laughing Gull I have slowly and decisively morphed into a sailor who is at heart a cruiser. For me a sailboat is now a way to live, and a way to explore. I really don’t care that much how fast I get someplace (though IF I am racing, I am RACING. Competitive genes. What can I say?).

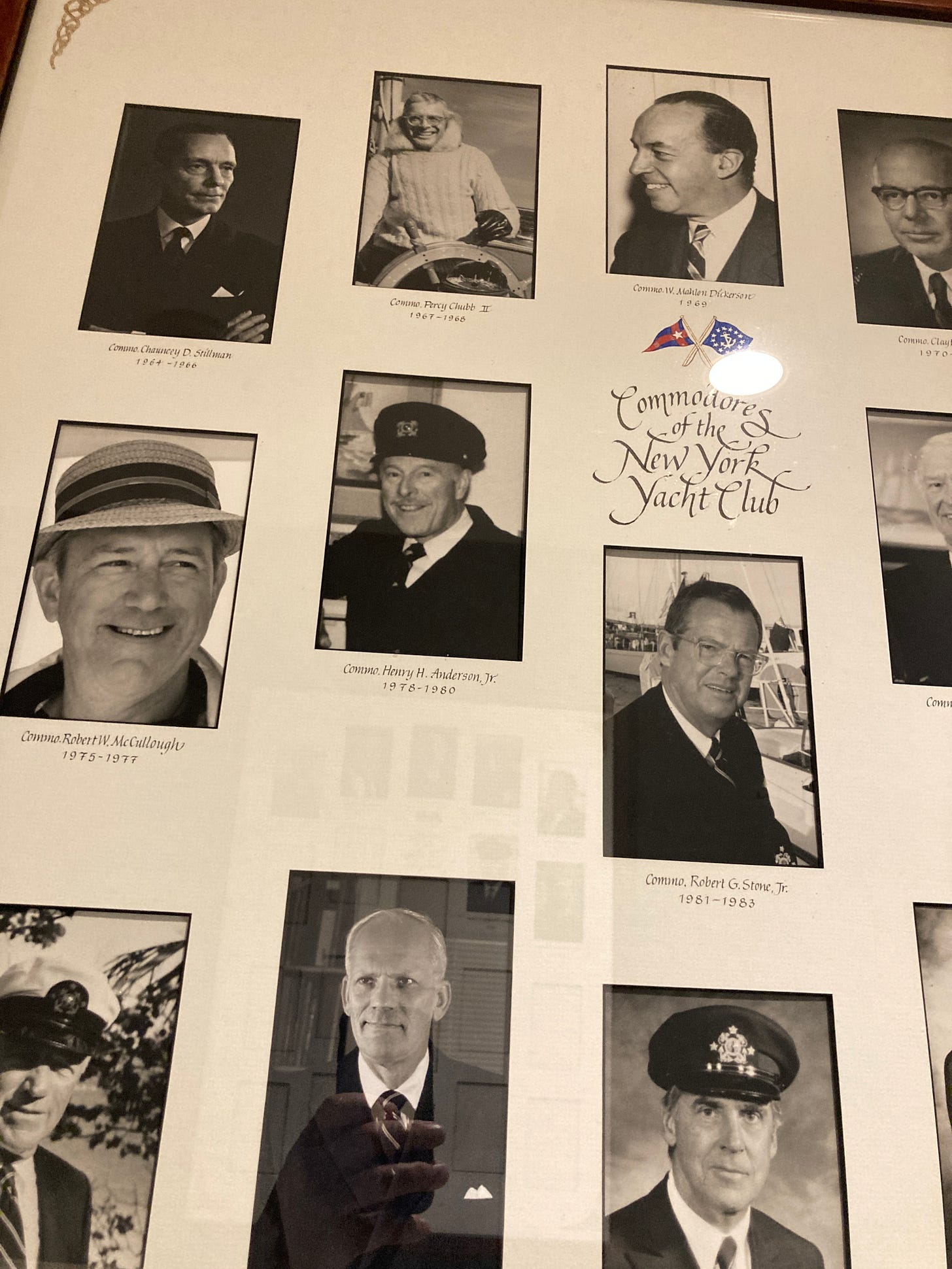

Sailboat racing also involves lots of yacht club immersion, which has long sparked conflicted feelings within the adult me. Many generations of my family had serious yacht club connections. I grew up spending time in yacht clubs, and some pretty swanky country clubs. In my youthful naivete and ignorance (possibly willful? I don’t know), I was completely oblivious to any cultural or social implications, aware only of the fantastic amenities at my disposal (due, I can admit with hindsight, only to the lucky lottery of my birth).

In our current times, though, with my increasingly jaded eye, yacht clubs mostly present to me as near-perfect aggregators—to the brink of caricature—of wealth and (almost exclusively white) privilege. If you want to find the sort of lifestyles that are having the greatest, and most egregious, impact on the planet, simply walk into a yacht club bar. I am trying to find another way to live, to redeem my long association with that sort of lifestyle. But within the wood-paneled walls of a yacht club I am a crank, an agitator, a defector. Still, obliviousness and willful ignorance persist. They should be symbols on every yacht club burgee.

Mattapoisett is an unassuming seaside town, with no elite yacht clubs in sight. The transition back to the soul-restoring life aboard Laughing Gull is rapid and welcome. The harbor, and a rock solid mooring provided by Triad Boatworks, have made Mattapoisett an excellent place to stash LG while I have been away. But it is wide open to the south, and the prevailing southwesterly breeze pushes a steady bobble into the harbor. The chop relentlessly bounces LG around, just enough to be annoying, and makes me eager to find a calmer anchorage from which to stage my move north though the Cape Cod Canal, and on to Maine.

July 2. Sippican Harbor. Marion, MA:

Three says ago I dropped the mooring in Mattapoisett, and made the short hop to this well-protected harbor. It is a good spot to jump into a flood tide that will shoot me through the Cape Cod Canal. When I was in college, my uncle (yes, a member of the New York Yacht Club) kept a Cape Dory 36 here in Marion. Though it seems insane to me in retrospect, he generously allowed me to take it out on cruises with my friends anytime he wasn’t using it. Some epic and often bacchanalian adventures ensued, from Block Island to Nantucket, and as far afield as Maine. We never did any damage to the boat, which I suppose proves my uncle’s judgement sound. But I suspect that was due more to luck than skill.

Like most of the best harbors of my younger years, there is no longer any room to anchor here. The harbor is jammed with moorings, most private, and a few available for transients. So I have been sitting on a mooring maintained by the Beverly Yacht Club, alongside an array of good-looking sailing boats. BYC is a relatively unpretentious club, though the membership would look at home in Newport, Oyster Bay, or Marblehead.

Like all old-school clubs they run an impeccable launch service, which makes trips ashore easy. I take advantage to try and start running again. Staying in excellent shape on a boat is turning out to be more challenging than I expected, and I miss that confident, wolfish, feeling of extreme fitness. But quickly am reminded by my left calf that I live in an aging body that does not easily adapt to something new. It is frustrating. With a little training my body can cycle 100 miles, and handle epic climbs. But I can’t run 2-3 miles consistently without tweaking something. There is an obvious solution: swimming. Yet, I resist it. Instead, I go paddleboarding to look at pretty boats.

Marion is a placid contrast to what is happening in the Windward Islands of the Caribbean, with the passage of the Hurricane Beryl. I have boundless sympathy for all sailors who are anywhere near its path. You do your best to avoid such dangerous and vulnerable moments, but Nature is implacable. Eventually, you get caught out and find yourself doing what you can to weather whatever is being thrown at you, your guts wrenched into a knot, and a cloak of fatalism keeping you sane. Beryl is in or near record territory for rapid intensification and strength, given how early we are in the hurricane season. Which is what you would expect given that surface sea temperatures have been breaking records for well over a year, as the oceans continue to try and absorb all the heat humanity is pumping into the atmosphere.

The media is naturally emphasizing how unprecedented this storm is. What they are not doing is explicitly and frequently connecting the unusual power and characteristics of this storm to human-generated climate change. This is a failure, because unless and until the global public better understands the implications of ongoing climate warming, humanity’s role in it, and how it will affect lives everywhere, the consensus in favor of rapid and consequential policy and lifestyle change will remain frustratingly elusive.

Hopefully, the consequences of Beryl—especially on local residents of the vulnerable islands in her path—will be recoverable. But this is the future. The more we do now, the better off we will be as the profound and catastrophic consequences of heating the planet continue to accelerate.

July 3. Provincetown, MA:

I woke up early, at 6 am. On the boat I trend into a rhythm that more closely follows the sun. Asleep by 10 pm, up by 6 am. The anchorage is dead calm, with not a breath of wind. The air is cool and humid. It’s a lovely morning and I sit in the cockpit drinking a cup of coffee, and contemplating whether I should push on to Gloucester or spend a few days in P-town. I haven’t been ashore here in a couple of decades, but my instinct is that, more than most places, it will be a July 4 zoo. I decide to pull the anchor and point my bow north again.

I follow the great, hooked, shore that wraps itself around Provincetown, dodging lots of fishing gear. Cape Cod Bay is a favorite feeding ground for the North Atlantic Right whale, a species which is slowly and needlessly being driven into extinction by ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement. I am surprised, and saddened, by the amount of gear I see in these waters. It is like the problem doesn’t exist. And if I am having to weave around numerous pots, and long line gear in the deeper water, it is easy to understand why all the whales frequenting these waters so often end up wrapped in fishing line (scientists estimate something like 85% of right whales run into fishing gear at some point in their lives).

As if to emphasize the point, I suddenly hear and see a whale spout just a few hundred yards from LG. There is nothing nicer than feeling that jolt of connection with a large, intelligent, whale. I’m not sure if it is a right whale or another species. But he or she is right in the middle of the traffic lane guiding big ships into Boston harbor. In fact, the Queen Mary 2 just passed by, doing 15 knots. It’s a lottery out here, and the whales often lose. More broadly, it’s a classic tradeoff between human commerce and industry, and a benign (and sublimely beautiful) species that has become collateral damage in our profit-dominated economic system. It’s the kind of trade-off that is being made all around the globe, to the impoverishment of the natural world and all the life webs which in the end help sustain humanity. Every species has inherent value, even if it is not commercial value. You can feel that instantly when you see a whale up close. It’s a failure of our system, and our way of relating to the planet, that we don’t take that into account.

I should arrive in Gloucester mid-afternoon. I’ve never been there by sea, so don’t really know what to expect. I hope it surprises me. In a good way.

Parting thought:

If you liked this post from Sailing Into The Anthropocene, why not subscribe here (free!), and/or hit that share button below? You can also find me on Instagram and Twitter.

To "redeem" your previous lifestyle and alleged "white privilege" you can only work from within. Standing outside the gate with a bullhorn always achieves precisely zero. So continue to be regarded as an "agitator" and "disrupter" but from inside the wagon!

Glad you're safe and back on LG