Let The Racing Season Begin...

A promising moment has arrived: the Chesapeake Bay Yacht Racing Association Green Book is out. It is, in fact, green. It is also digital. Most important, it is the official catalog of all sailboat races scheduled on the Chesapeake Bay this year. It means that warmer weather and lots and lots of time on the water are in the offing. After a long, socially-distanced winter it could not be more welcome.

Last year was about setting up Moondust (the Beneteau 36.7 I co-own) for shorthanded racing and settling in at the bottom of the learning curve to sort things out. This year is about climbing the learning curve as fast as I can. I used to prefer small, one-design racing. A J-22. Then a Laser. I didn’t want to buy big-boat racing sails or organize big-boat crews. I didn’t want to fuss about ratings—if you beat a boat you beat a boat. Shorthanded racing on Moondust solves one of these objections (building a big crew). I still had to buy some sails, and I definitely get sucked into doing time-allowance math around the race course (on the plus side, perhaps that will help stave off cognitive decline).

Turns out I don’t mind, though. Because I love the challenge of shorthanded sailing. You alone, or you and just one crew, have to do everything—all the sail-handling, boat-handling, navigation and tactics. You are one-hundred percent engaged. You have no time or space to worry about anything other than getting a boat around the course as fast as you can. That is my idea of fun.

To get faster this year, I made one offseason tweak. The 36.7 is designed as a symmetrical spinnaker boat, and in a moderate breeze will get downwind fastest (VMG—Velocity Made Good) by sailing deep with a symmetric kite. But last October, in the Annapolis Yacht Club’s Doublehanded Distance Race, Moondust got killed on long, very light wind, tight reaches. The genoa I have just isn’t big enough or light enough in those conditions. And the symmetrical spinnaker just wouldn’t let us sail the higher heading we needed keep aiming at the marks. So I bought a used 36.7 asymmetrical spinnaker from a 36.7 sailor in Chicago. I think it will be great for light air reaching, and maybe also for heavy air downwind. I can either fly it off the pole if I want to sail deeper (and don’t think I will have to gybe—which would be complicated for a shorthanded crew), or tacked down to the bow. Will this work well? I don’t know yet. It’s not going to be like The Whomper.

But it will be at least a Whimper. I’ll try different setups with different wind speeds and angles to find out how to best use it. That is also my idea of a good time.

The Green Book is chock full of races. Moan about or mock the brownish water and scorching mid-summer doldrums of the Chesapeake Bay, its long and packed racing calendar is a racing sailor’s nirvana. What is notable this year is the number of shorthanded races (which will make the young and growing Chesapeake Singlehanded Sailing Society happy). For example, the three-day Annapolis NOOD regatta (usually the first big regatta of the season) will feature a doublehanded long-distance race on Day 2. I’m already registered.

Without trying very hard I compiled a list of 15-plus weekend races that will include a shorthanded class. Throw in a COVID vaccine in the next month (I hope) and life is about to be pretty good.

Plans for Wednesday Night Racing in Annapolis are also firming up. That will be full crew, and just another excuse to be out on the water and learn how to make Moondust go faster. WNR can be a pandemonium of 100 or more racing boats trying to survive each other within the confines of the Severn River, especially if it is windy. There will be plenty of tales to tell, and I haven’t raced on Wendesday nights in 20 years. But my recollection is that can feel sorta like this:

So stay tuned for lots of actual, on-the-water action, starting mid-April.

America’s Cup Aftermath: It’s over. The Kiwis won, as expected, by getting faster and better at racing their boat over the course of the series. The Italians did pretty well given a boatspeed disadvantage, and had the impossible task of needing to start and sail perfectly to win (which they sometimes managed). The boats were incredible, the tactical nuances were compelling, and the sailors showed personality and grit. Screw all the moaners who can’t adapt to flying boats. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and look forward to the next cycle in 3-4 years.

The Wisdom Of Whales: Humanity often sees itself as separate and apart from the planet’s other species, especially when it minimizes and misunderstands nonhuman intelligence. But every time research and experience reveals another species to be more intelligent than we assumed (and research almost always reveals more intelligence, not less), that gap between humanity and the natural world shrinks. Which is a good thing if we are to finally grasp the single most important point about life on Earth, which is: Everything Is Connected. So this story about how hunted sperm whales learned to avoid whaling ships caught my eye:

The paper, published by the Royal Society on Wednesday, is authored by Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell, pre-eminent scientists working with cetaceans, and Tim D Smith, a data scientist, and their research addresses an age-old question: if whales are so smart, why did they hang around to be killed? The answer? They didn’t.

Using newly digitised logbooks detailing the hunting of sperm whales in the north Pacific, the authors discovered that within just a few years, the strike rate of the whalers’ harpoons fell by 58%. This simple fact leads to an astonishing conclusion: that information about what was happening to them was being collectively shared among the whales, who made vital changes to their behaviour. As their culture made fatal first contact with ours, they learned quickly from their mistakes.

It’s mind-opening to consider the possibility that sperm whale culture and communication allowed sperm whales to respond to the whaling threat. Unfortunately, today’s whales are not primarily threatened by whale ships, but by ship strikes and fishing gear. And in today’s ocean there is no escaping either commercial ship traffic or global fishing fleets.

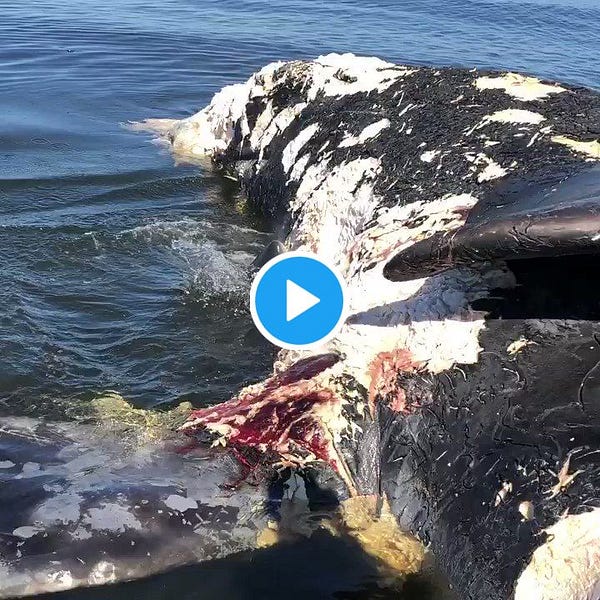

Sad Circle Of Life: A case in point is the North Atlantic Right Whale called Cottontail, who died from fishing entanglement. Last seen months ago, Cottontails floating corpse was recently discovered by a fisherman off the coast of South Carolina, being mauled by Great White sharks. Cottontail is just the latest death in the relentless and cruel decline of the right whale due to ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements. But Great Whites are endangered too, so at least another species got some benefit from Cottontail’s needless and sad death.

The scene was pretty raw, Nature doing Nature. But we should see things as they are (though I could do without the enthusiastic tone). More images and video here...

Right whales are innocent bystanders to consumption and globalization (which are crowding the oceans with large ships), as well as the thriving crab and lobster fisheries (which mean a forest of vertical lines in the water through much of the right whale habitat). Efforts to protect them so far haven’t succeeded in slowing their mortality rate enough to save the population. Apart from supporting more stringent restrictions on ship speeds and pot fishing, we probably should think harder about all the stuff we think we need to buy and whether we really need to eat so much crab and lobster.

There Be Amazing Sea-Creatures: Take care of ocean, people. It contains wonder and multitudes.

That’s all for today. If you would like to receive the latest Wetass Chronicles in your inbox when they are published, please subscribe here.