Laughing Gull is bouncing around on her anchor here in St. George’s harbor. It is a fully protected anchorage, surrounded by land masses and a narrow cut open to the sea. But there is plenty of fetch to kick up a decent boil when the wind gets up. The resulting waves reflect off all the concrete and rock lining the shore, turning the harbor into a choppy, confused, bathtub. Add in the swirl of tidal currents and all fantasies of a postcard idyll at anchor are shaken into oblivion. The ocean is a dynamic environment, and it likes to send reminders. Maybe that is a good metaphor for my life right now.

Crew for the passage to the Azores arrives in 10 days, and we will depart as soon after that as the weather allows. I am feeling a bit antsy because I can’t think of that many things to fix or prepare—which doesn’t feel quite right in advance of a nearly 2000-mile ocean crossing. I have to provision to feed four people for two weeks, which will be a job, and take on fuel and water. Still, LG seems mostly ready. I do too.

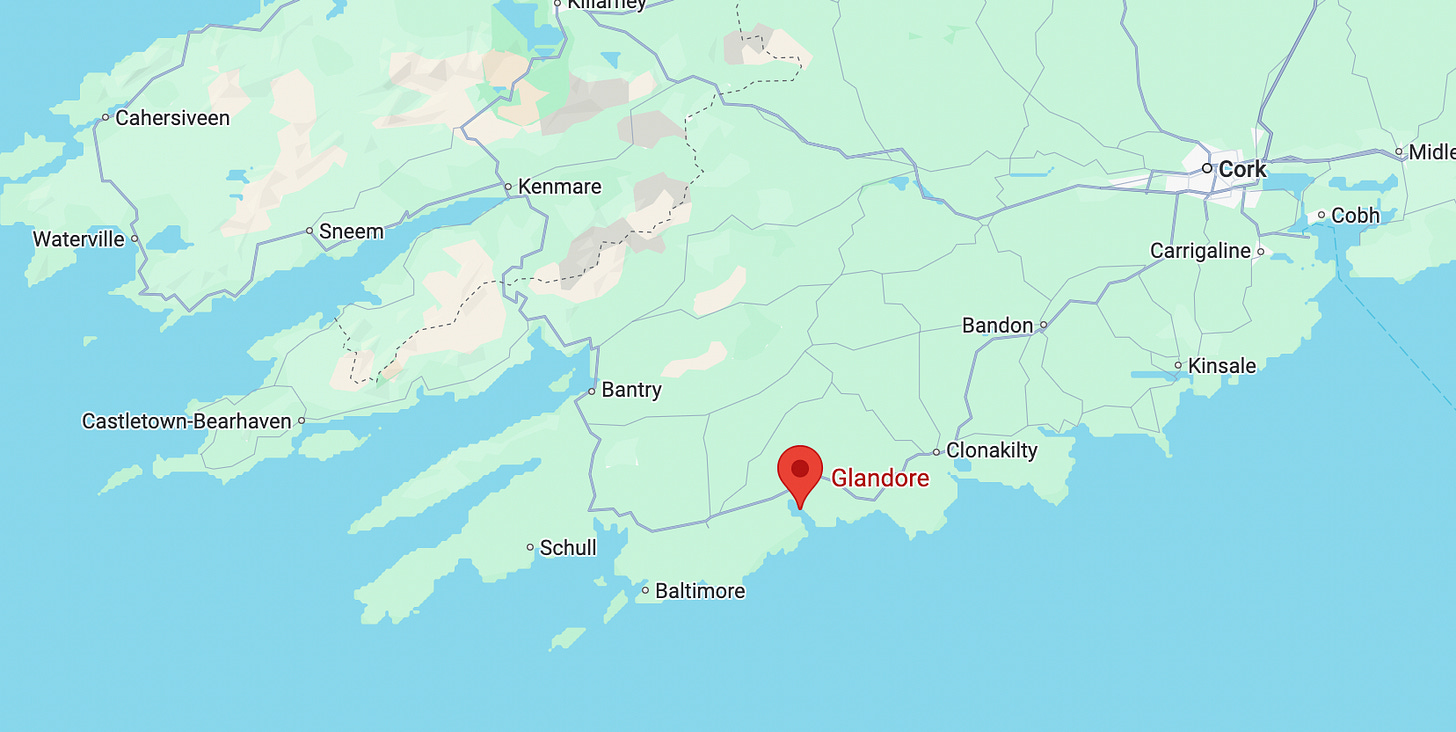

The plan is to sail Laughing Gull into the familiar harbor of Glandore, Ireland around mid-July. Once there, things will change quite a bit. Since I bought LG in May 2022, I have been more aboard than ashore—experimenting with ways of living that seem simpler and more meaningful in our current troubled epoch. It has been a thoroughly necessary, and immensely rewarding, odyssey. I learned lots of things about myself, and how I want to think about the future. And I followed the sun, the winds and the stars between north and south latitudes.

Once I arrive in Ireland, Laughing Gull will be based in northern Europe for a spell and the liveaboard odyssey will morph into something different. I plan to lay LG up during the winters, and set off on sailing adventures (Norway? Sweden? Scotland? The Faroes?) during the summers. There is no easy delivery to Florida or tropical latitudes from Northern Europe. In any case, I am ready for a life that is more balanced between sea and land, and opens up opportunities for more exploration ashore.

It will be a big change. I look forward to having the time and space to try and undertake more focused and disciplined writing, either in Ireland (a land of storytellers) or in other nooks and crannies of Europe yet to be identified. I have to admit I enjoy not knowing everything about the future, or having a firm plan. It is always nice to have the freedom to tack and change course according to the winds and weather life presents.

The timing feels right. I set out on Laughing Gull to answer some questions, and I have mostly found the answers I needed. Plus, while I enjoy some solitude I want to be better connected to friends and family. It is too easy to sink into your own world out here, cut off from reality and social connection. Being off the boat for extended stretches makes it a lot easier to be part of the human community—which mostly prefers to live on land—we all need to thrive and be happy.

While in Bermuda, with the last big passages of my odyssey just ahead of me, I’ve been trying to distill the key principles that the ocean and living afloat have clarified for me. Principles which I can apply (which anyone can apply) no matter where or how I live. It feels grandiose to think like this, and especially to say them out loud. But I am trying to get more comfortable writing about what goes on in my head and in my life, after decades of journalism in which the writer stays out of the story. So without much nuance (for now), and without much detail (for now), here are three insights which I am putting at the center of my thinking and actions.

The first is: Everything Is Connected. Humanity, though divided artificially by borders and beliefs, is a single species with a universal destiny (which hopefully doesn’t involve fleeing to Mars). And everything humanity does has impact on other species and the ecosystems which sustain us and create a liveable planet. Burning fossil fuels in one place bleaches coral reefs in another. The container shipping needed to meet the high demand for goods kills whales due to ship strike, and dead whales alter the carbon cycle in the oceans. Factory farms raising poultry spark and propagate bird flu that decimates wild bird populations as far away as the polar regions. The plastic and chemicals in modern economies can now be found everywhere. We are not apart from Nature. We are integral to Nature. And Nature is integral to us. Its fate, and our fate, are inextricably linked. Earth, with all its life, is a beautiful, sublime, infinitely complex, and exquisitely calibrated, mechanism. How we live and what we do matters. Everything is connected.

This is not a new insight, but it is often forgotten or wilfully ignored in pursuit of profit. What is new, or at least more recent, is that humans, with our swelling numbers and clever technologies, have sufficient weight to disrupt and damage this miraculous Earth system (hence “the anthropocene”). It is a system that for tens of thousands of years has provided the perfect climate and ecological basis for humans to thrive, so the harmful trajectory we are on now seems tragically short-sighted and self-destructive. If human culture, economics, and politics better reflected this truth, the future would be very different. And more hopeful.

The second, which partly flows from the first is: Minimalism Is A Superpower. Life on a sailboat teaches you this truth in a hundred different ways. Consuming less, spending less, polluting less, is a trifecta of good. And good for the soul. Decades of increasingly sophisticated marketing have been dedicated to the idea that buying (more) stuff will make you happy. Having food, shelter, and the essentials in life provide a foundation of happiness and wellbeing. Beyond that, the increments of happiness consumption brings decline rapidly. Time to think, be with people you care about, and spend outdoors is a better recipe for happiness and living in harmony with the planet. The less you buy, the less you own, the less you have to manage, the less you have to earn, and the more time you have for the truly important things.

Finally: Compassion Is Key. The human experiment is currently heading in a dark direction, propelled by anger, partisanship and hatred (which are all turbocharged, and sometimes wholly generated, by social media—arguably humanity’s single most regrettable invention). Compassion (and a desire to understand and accept) can heal divisions, clarify and empower solutions, stop wars. But it is not just compassion between individuals, groups, and nations that is needed. It is compassion for other species, compassion for all the living world and the ecosystems which support life on Earth, which is also critical. Relentless exploitation and extraction for short-term commercial profit are a ticket to a grim and nihilistic nowhere. Everything is connected. To thrive into the future, we have to stop doing damage. We have to care about more than human interests. We have to expand the circle of our moral concern to all living things and ecosystems.

This is all grossly simplified, and of course there are endless complex tradeoffs that have to be navigated. But you can’t make choices and evaluate trade-offs without first knowing what is important and what you should care about. That’s where my head is now, where my odyssey so far has taken me. The ideas are not fixed. They can evolve and change. They are a starting point. New ideals or principles are welcome (let me know in the Comments). Play around with them, as I am, and see where it takes you.

Whatever the right answers, it just feels like we need a very different way of thinking about our lives and our relationship to the planet and everything else on it. Maybe that is the most important insight of all that Laughing Gull’s odyssey helped confirm. We are at an inflection point in human history, and face a test of whether we can transcend old ideas and ways of thinking. So don’t listen to the marketers. Definitely don’t listen to cable news and social media. Tune out the demagogues and disinformers. Find your own guide stars and make your own choices accordingly. We’ll all be better off.

Anthropocene Notes:

Accepting responsibility: A recent study concludes that the wealthiest 10% of humans on the planet (which is basically anyone who is middle class on up in any developed country) are responsible for almost two-thirds of global warming since 1990:

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, uses a field of climate science called “attribution” to determine the contribution of the world’s “wealthiest population groups” to climate change through the greenhouse gases they emit.

The authors also calculate the contribution of these high-income groups to the increasing frequency of heatwaves and droughts.

For example, the study finds the wealthiest 10% of people – defined as those who earn at least €42,980 (£36,605) per year – contributed seven times more to the rise in monthly heat extremes around the world than the global average.

In another finding, the Amazon rainforest faced a threefold increase in the likelihood of droughts over the period studied, most of which was driven by the wealthiest 10% of the world’s population.

The authors also explore country-level emissions, finding that the wealthiest 10% in the US produced the emissions that caused a doubling in heat extremes across “vulnerable regions” globally.

What should we do with this reality? Cass Sunstein, in his new book “Climate Justice”, has some ideas.

Rutger Bregman also wants big ideas and big change, and he is calling on all of us, in his new book, to have Moral Ambition. Bregman has also started the School For Moral Ambition to encourage the world’s best and brightest to work on the biggest problems humanity faces. Good interviews about his ideas here, and here. Here’s how Bregman first came to people’s attention:

If you eat seafood, oysters and mussels are the most sustainable choice. Eater explains why good oysters cost what they do:

At places like the Lonely Oyster in Los Angeles, you could pay as much as $6 for a sustainably sourced Blue Pool oyster pulled from the waters of Hama Hama, Washington. And while some may chalk these sometimes eye-popping prices up to historic inflation or price-gouging on the behalf of restaurants or their suppliers, the factors that go into oyster pricing are actually much more complicated than that. It used to be that the vast majority of oysters were caught wild, but due to a wide range of issues like overfishing and pollution, the global oyster population has declined by an estimated 85 percent over the last hundred years.

As a result, oyster farmers on all three American coasts have stepped in to meet the demand, and oyster farming is a whole lot more difficult than you might expect. Before an oyster even makes it onto one of those fancy towers at your favorite seafood restaurants, there’s a whole lot of money — and labor — that goes into that tiny shell.

If you liked this post from Sailing Into The Anthropocene, why not subscribe here (free!), and/or hit that share button below? You can also find me on Instagram and BlueSky.

Thank you Tim. Beautiful thoughts. I am reminded of passage in Bewilderment (R Powers):

There are four good things worth practicing.

Being kind toward everything alive. Staying level and steady. Feeling happy for any creature anywhere that is happy. And remembering that any suffering is also yours.

Safe passage!

With all this bad news plus war and politics, it's easy to think that one person cannot make even a minuscule difference. How to convince people that it does? The problem set is the only one that can afford a $6 oyster.

Most certainly, everything is connected. Fair winds to you Tim, enjoy the passage back to land! ~J